Learning styles are all the rage these days. You’ve heard someone say, or may have said yourself, “I’m a visual learner.” That is an example of a learning style. The idea is appealing. Some companies claim they can use learning styles to create a custom curriculum for each of your employees, which usually requires you spending valuable resources on their expensive tests to learn your employees’ learning styles. Unfortunately, these claims don’t stand up to scientific research on the subject, which finds learning styles don’t exist.

What are learning styles?

What are learning styles?

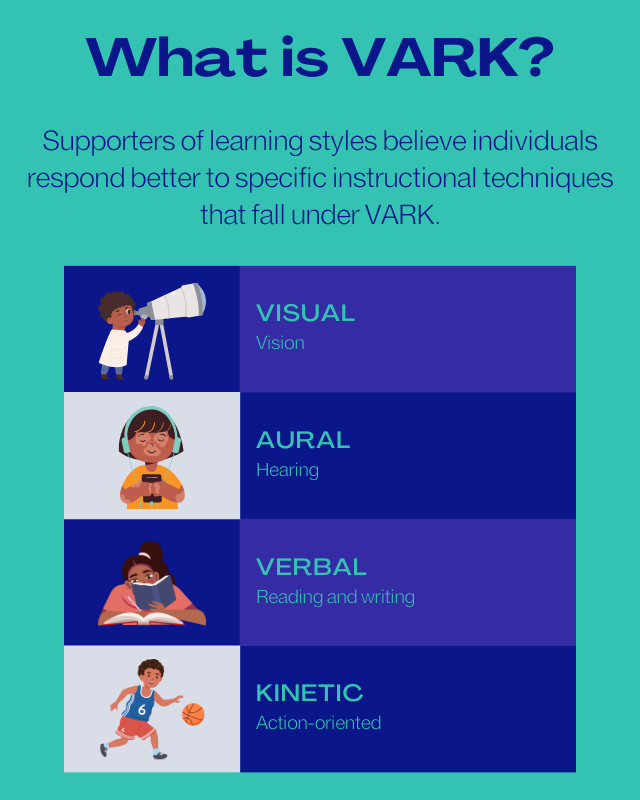

Supporters of learning styles believe individuals respond better to specific instructional techniques – and there are over 71 styles that fall under VARK:

- Visual (vision). Visual learners understand and retain information best by seeing it in a visually appealing way, not in a written format.

- Graphic displays such as charts, illustrations, graphs, animated videos, documentaries, demonstrations, and color-coded information.

- Aural (sound). Aural, or auditory, learners take in information best by hearing it. They prefer to listen to a presentation rather than write notes and often need a quiet environment so they can listen intently, with few distractions.

- Lectures, recordings of notes, podcasts, audio books, discussions about new information, and mnemonics.

- Verbal (reading and writing). Verbal learners benefit most from reading and writing about new information. They often create lists, read definitions, and craft beautifully organized color-coded notes.

- Notes summarizing textbook readings, class notes, presentations, solitary studying, and story-writing.

- Kinetic (action-oriented). Kinetic, or kinesthetic, learners are tactile learners who learn best by touching and doing things. They use a hands-on, “trial and error” approach to learning and learn better in short bursts, rather than sitting at a desk for lengthy periods of time.

- Experiments, physical activity, flash cards, regular study breaks to stretch legs.

How do people implement VARK?

These descriptions are only the beginning of the VARK approach. The next step is combining styles to activate learning in an individual. For example, someone who takes a VARK test may be “kinetic-aural,” meaning they learn best in action-oriented courses led by a facilitator, or an eLearning course that plays specific sound effects to reinforce actions. The VARK theory maintains that courses customized to the individual learner’s style are the best training for that person. However, it also suggests that a course designed to cater to one learning style is detrimental to other types of learners.

What does science say?

What does science say?

According to a major 2008 report, Learning Styles: Concepts and Evidence, there is no evidence that learning styles exist. The authors reviewed the existing literature on learning styles and found the studies that “prove” the existence of distinct types of learners did not use industry-standard randomized research to make their “evidence” credible.

Nearly all studies claiming to be evidence of learning styles do not follow standards of scientific research:

- They do not classify learners into categories.

- They do not randomly assign learners to use one of many learning methods.

- They do not ask participants to take the same test at the end of the experiment as they did in the beginning.

If learning and teaching styles should mesh, learners who use a specific style should learn better with instruction paired to that style. Such results can be measured by comparing results of the same test taken before and after a session. Instead, very few of these studies tested these outcomes. Although some did, their evidence was contrary to their hypothesis.

Nancy Chick, former Assistant Director of Vanderbilt University’s Center for Teaching, says, “Despite the popularity of learning styles and inventories such as VARK, it’s important to know that there is no evidence to support the idea that matching activities to one’s learning style improves learning.”

While learning styles remain popular with educators and the public in general, more people now use multiple intelligences (MI) as a better educational tool.

What are multiple intelligences?

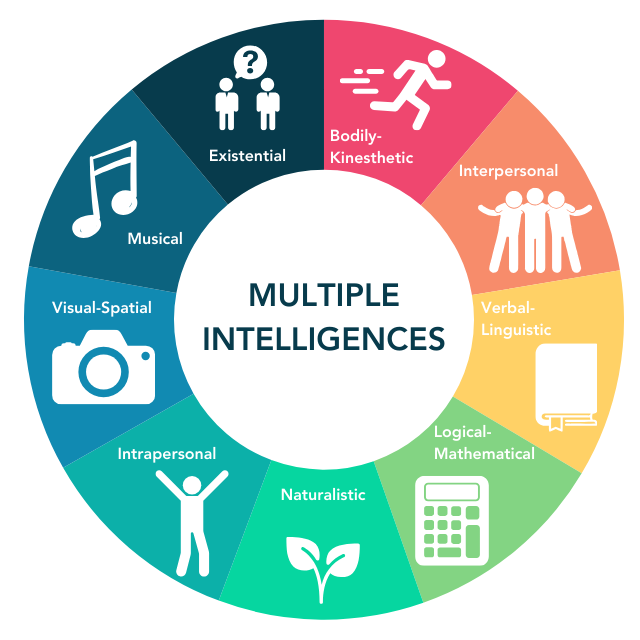

Howard Gardner’s (Ph.D.) Theory of Multiple Intelligences is the current big thing in the education arena. Don’t think of this as another “learning style” approach. According to Gardner, there is “no persuasive evidence that the learning style analysis produces more effective outcomes than a ‘one size fits all approach.’” Together with Elisabeth A. Hobbs, Gardner developed seven separate intelligences. Today there are nine, and the list may continue to grow.

Gardner’s Multiple Intelligences, in a nutshell:

- Verbal-linguistic: Well-developed verbal skills and sensitivity to sounds, meanings, and rhythms of words.

- Logical-mathematical: Aability to think conceptually and abstractly, capacity to discern logical and numerical patterns.

- Spatial-visual: Capacity to think in images and pictures, to visualize accurately and abstractly.

- Bodily-kinesthetic: Ability to control one’s body movements and to handle objects skillfully.

- Musical: Ability to produce and appreciate rhythm, pitch, and timber.

- Interpersonal: Capacity to detect and respond appropriately to the moods, motivations, and desires of others.

- Intrapersonal: Capacity to be self-aware and in tune with one’s feelings, values, beliefs, and thinking processes.

- Naturalist: Ability to recognize and categorize plans, animals, and other objects in nature.

- Existential: Sensitivity and capacity to tackle deep questions about human existence.

According to Gardner, presenting learning materials in multiple ways allows all students in a class to learn to their best ability, whether the subject is math, science, history, art, music, etc. Not only does this help them learn, but it also allows educators to increase and refine their mastery of a subject – like when a student asks a teacher to communicate knowledge in a different manner than they are used to. Doing so helps educators rethink how they convey knowledge to their students.

The basic idea is simplicity itself. A belief in a single intelligence assumes that we have one central, all-purpose computer – and it determines how well we perform in every sector of life. In contrast, a belief in multiple intelligences assumes that we have a number of relatively autonomous computers – one that computes linguistic information, another spatial information, another musical information, another information about other people, and so on… There is strong evidence that human beings have a range of intelligences and that strength (or weakness) in one intelligence does not predict strength (or weakness) in any other intelligence.

Howard Gardner, author of "Multiple Intelligences: The Theory in Practice."

Everyone has strengths and weaknesses in various intelligences, so educators should decide how best to present material depending on the topic and that specific class of students. One of the best results of teaching to MI is triggering a student’s confidence in developing areas where they are less strong.

How do we apply MI in corporate training?

If we identify the learning components motivating an individual to contribute to their jobs and companies more effectively, we increase the chances of successfully implementing training. We must adapt training to reflect employees’ different intelligences. The best way is to create interactive and collaborative training that corresponds to the many ways adults learn.

Detractors criticize Gardner’s theory, believing it confines learning to one type of intelligence. On the contrary, the MI theory maintains that everyone possesses multiple abilities to different degrees. Gardner emphasizes that all intelligences are equally valuable, as different situations call for a distinct set of skills.

What are the benefits of using the MI Theory for training?

What are the benefits of using the MI Theory for training?

The benefits of creating training for MI include:

1. Increasing the impact of training by capitalizing on the learners’ strengths.

- Certain job roles favor specific types of intelligence, but that one type is not necessarily superior to others. How one applies their strengths matters more.

- Example: Which salesperson will be more successful: one who is eloquent and delivers persuasive arguments, or one who is an introspective listener who intuitively understands what a customer needs? Well, both are likely to succeed if they embrace their natural strengths. Neither is more likely to succeed than the other.

- According to a Gallup poll, companies that focus on maximizing employee strengths see a profit increase of up to 29 percent. That poll also shows that workers who use their strengths daily are 85 percent more productive and six times more engaged than those who do not.

2. Boosting employee creativity by embracing an interdisciplinary learning approach.

- Sometimes we think people who don’t think the same way we do have an intellectual or learning disability.

- Example: As a young man, Albert Einstein was considered by employers and others to be “intellectually handicapped.” He’s now considered one of the most creative geniuses of all time. His creative thinking stumped society when he was young, as humans so often tend to think badly of those who are different from us. That creative, unusual way of looking at things enabled him to make incredible discoveries.

- CEOs consider creativity to be one of the most valued skills in the workplace. However, Gallup research shows that 78 percent of workers think they are not living up to their creative potential. Embracing an interdisciplinary approach to training and working with others can bridge that gap.

3. Embracing learner diversity to create a truly inclusive and personalized training environment.

- A team made of people from diverse backgrounds and skills sets can achieve big things. This is why diversity initiatives are a top priority among professionals.

- Example: Lenovo is considered the world’s largest PC vendor and has always been an inclusive company. The company constantly creates new and innovative ideas in its industry. It scored a perfect 100 on the Corporate Index for LGBTQ Equality and focuses on creating a place of inclusion for its employees.

- A recent McKinsey report finds that companies in the top quartile for gender diversity on executive teams are 25 percent more likely to see above-average profitability than companies in the fourth quartile. This is up from 21 percent in 2017, and 15 percent in 2014.

How can corporate training initiatives use the MI theory?

Trainings need to cover the many intelligences and offer learners the opportunity to test their skills and knowledge, but how? Create training that includes an array of strategies so that all learners are using their strongest intelligences while improving their weakest ones.

For example, one course may combine:

- Asking learners to read a synopsis of a new project, then explaining it to others (Verbal/Linguistic).

- Using logic puzzles to enable learners to think at various levels of abstraction (Logical/Mathematical).

- Re-arranging the room layout at each break to help learners experience variety (Visual/Spatial).

- Playing specific music related to the subject matter for each learning session (Musical/Rhythmic).

- Asking the group to form a circle and give a ball to one person. They will say one message they have learned from the training, then toss the ball to another person, and the activity repeats (Bodily/Kinesthetic).

- Asking learners to introduce themselves to someone they don’t know. Then ask them to introduce that person to the group while in session (Interpersonal).

Offering learners some quiet time to reflect on their ideas and write them down (Intrapersonal).

If learning styles aren’t backed by science, why do so many people use them?

Humans tend to resist and dislike change. While there is no evidence that learning styles exist, surveys show that 80-95 percent of people in the U.S. and other industrialized countries still use the concept of learning styles. There seems to be a disconnect in the conversation: critics of the learning styles approach are not saying differences don’t exist between students, or that tailored teaching approaches aren’t ever helpful. Rather, they acknowledge individual differences according to the MI approach.

The good news is that the MI approach continues to gain acceptance among educators. However, there are a few caveats:

- MI is still often conflated with learning styles. We all have learning preferences, but often use a combination of intelligences to learn.

- MI is not about distinct traits but how an individual combines them when learning.

- Intelligence is not fixed. People can improve their intelligence in any area.

Gardner argues that MI should not, in and of itself, be an educational goal. Instead, we offer a few evidenced-based dos and don’ts for applying MI theory in training:

Do:

- Give students many ways to access information. Your sessions will be more engaging, plus learners are more likely to remember information presented in several ways.

- Individualize trainings, to an extent. Avoid a one-size-fits-all method and think about learners’ needs and interests.

- Incorporate the arts into trainings. We often focus on linguistic and logical intelligences, but we can help individuals grow by allowing them to express themselves in ways that are natural to them.

Don’t:

- Label learners with one type of intelligence. Pigeonholing students denies them the opportunity to learn at deeper levels. Labels such as “book smart” or “visual learner” can be harmful and discourage learners from developing their weaker skills.

- Confuse MI with learning styles. A popular misconception is that learning styles are a good application of the MI theory. It doesn’t matter what sense we use to take in information. What matters is how our brain processes that information.

- Try to match a lesson to a student’s perceived learning style. Students may prefer how material is presented, but there’s little evidence that matching materials to a preference will improve learning. When educators do that, they assume that there’s one best way to learn, which may prevent students and teachers from using strategies that work. Gardner says, “When one has a thorough understanding of a topic one can typically think of it in several ways.”

Creating trainings that include variety leads to more success in moving information from your learner’s short-term memory into long-term storage than using boring trainings meant for one or two intelligences. A multi-faceted approach turns passive employees into active participants, resulting in employees learning and implementing more from training. Employers see a better return on their investment from quality, multi-faceted training than they do from old-school training.

Contact MATC Group today to learn how we can help you develop cutting-edge, engaging, and effective training!

Related Blogs

From Concept to Completion: Microlearning Design Best Practices

Is Your eLearning Accessible to Everyone?

Seven Myths About eLearning Debunked

Resources

Broadbent, Katie. “4 Different Learning Styles: The VARK Theory.” Melio Education. 4/7/2021. Accessed 6/12/2023. https://www.melioeducation.com/blog/vark-different-learning-styles

Carroll, Patrick. “Learning Styles Don’t Actually Exist, Studies Show.” FEE Stories. 8/12/2022. Accessed 6/12/2023. https://fee.org/articles/learning-styles-don-t-actually-exist-studies-show.

Dixon-Fyle, Sundiatu, Kevin Dolan, Dame Vivian Hunt, and Sara prince. “Diversity wins: How inclusion matters.” McKinsey & Company. 5/19/2020. Accessed 6/13/2023. https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/diversity-and-inclusion/diversity-wins-how-inclusion-matters

“Gardner’s Theory of Multiple Intelligences & Workplace Learning.” Growth Engineering. 9/16/2021. Accessed 6/12/23. https://www.growthengineering.co.uk/gardners-theory-of-multiple-intelligences-workplace-learning/

“Howard Gardner’s Theory of Multiple Intelligences.” Instructional Guide for University Faculty and Teaching Assistants. Northern Illinois University Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning. 2020. Accessed 6/12/23. https://www.niu.edu/citl/resources/guides/instructional-guide/gardners-theory-of-multiple-intelligences.shtml

“Learning Styles Debunked: There is No Evidence Supporting Auditory and Visual Learning, Psychologists Say.” Association for Psychological Science. 12/16/2009. Accessed 6/12/23. https://www.psychologicalscience.org/news/releases/learning-styles-debunked-there-is-no-evidence-supporting-auditory-and-visual-learning-psychologists-say.html

McPheat, Sean. “The Use of Multiple Intelligences in the Training Environment.” MTD Training Group. 10/8/2018. Accessed 6/12/23. https://www.mtdtraining.co.uk/multiple-intelligences-training-environment/

Rigoni, Brandon, Ph.D. and Asplund, Jim. “Developing Employees’ Strengths Boosts Sales, Profit, and Engagement.” Harvard Business Review. 9/1/2016. Accessed 6/12/23. https://hbr.org/2016/09/developing-employees-strengths-boosts-sales-profit-and-engagement

Sorenson, Susan. “How Employees’ Strengths Make Your Company Stronger.” Gallup. Accessed 6/12/2023. https://www.gallup.com/workplace/231605/employees-strengths-company-stronger.aspx#:~:text=People%20who%20use%20their%20strengths,into%20human%20behaviors%20and%20strengths

Strauss, Valerie. “Howard Gardner: ‘Multiple intelligences are not learning styles.” The Washington Post. 10/16/13. Accessed 6/12/23. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/answer-sheet/wp/2013/10/16/howard-gardner-multiple-intelligences-are-not-learning-styles/

Terada, Youki. “Multiple Intelligences Theory: Widely Used, Yet Misunderstood.” Edutopia. 10/15/2018. Accessed 6/12/2023. https://www.edutopia.org/article/multiple-intelligences-theory-widely-used-yet-misunderstood/

“Top Companies With Robust Diversity and Inclusion Programs.” Melyssa Barrett. Accessed 6/12/2023. https://melyssabarrett.com/top-companies-with-robust-diversity-and-inclusion-programs/